Book Review: Andrea Del Sarto: The Renaissance Workshop in Action

Visual arts blogger and art historian, Nigel Ip reviews the catalogue from Getty publications, Andrea Del Sarto: The Renaissance Workshop in Action - a book which allows him to appreciate and savour Del Sarto's creative vision and drawing genius.

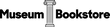

Andrea del Sarto: The Renaissance Workshop in Action (by Julian Brooks with Denise Allen and Xavier F. Salomon, with essays by Alessandro Cecchi, Dominique Cordellier, Marzia Faietti, Yvonne Szafran and Sue Ann Chui, Sanne Wellen, and a contribution by Marcia Steele. 236 pp. incl. 123 col. + b. & w. ills.) is the companion book to the exhibition held at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 23 June – 13 September 2015, and the Frick Collection, New York, 7 October 2015 – 10 January 2016.

In the city of Florence, there is one artist whose works are plentiful but rarely visited by most tourists: Andrea del Sarto. The son of a tailor (sarto), Andrea first trained with a goldsmith at the age of seven, before spending three years with the now-obscure painter Andrea di Salvi Barile. Afterwards, he entered the workshop of Piero di Cosimo, one of the most significant artists of the time, who respected Andrea’s aptitude for handling colour and his studious mindset. These two qualities are prominently revealed to readers of Andrea del Sarto: The Renaissance Workshop in Action, published to accompany the 2015/16 exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Frick Collection.

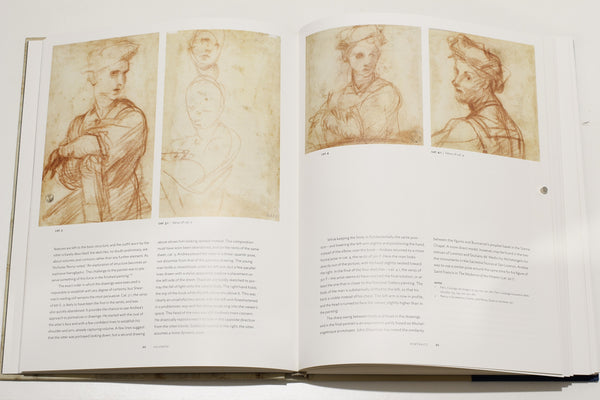

The introduction by Julian Brooks provides an excellent overview of the artist’s career, major influences, and notable qualities in his works: full of diagonals and gestures, sumptuous colours and fabrics, and exhibiting harmonious compositions whilst evoking grandeur. Brooks continues with a sample list of the ‘innumerable’ disciples in Andrea’s workshop, including Jacopo Pontormo, Giorgio Vasari, Francesco Salviati, and Rosso Fiorentino. The diversity of styles produced by each of these individuals leads one to suggest that Andrea’s workshop did not operate in the same manner as other workshops, where pupils were taught to paint under a single style dictated by the master. As Brooks rightly notes, there is little to no detailed evidence regarding the structure of Andrea’s workshop nor any insight into its delegation of labour. Fortunately, roughly 180 drawings by Andrea have come down to us, each allowing us a glimpse of his creative vision, command of draughtsmanship, and interest in sculpture.

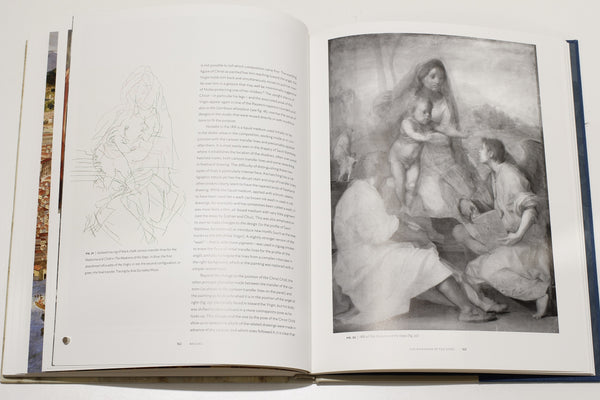

Brooks has dedicated the rest of his introduction to exploring the role of drawings in Andrea’s process, from compositional sketches and detailed life studies to the production of time-consuming cartoons for transfer onto wooden panels or plastered walls. However, Andrea’s experiments never quite stopped at the cartoon stage, usually considered the final planning stage before one begins to paint. Instead, he continued to dramatically alter his compositions after this stage until he was satisfied.

The catalogue is comprised of five thematic essays and two groups of catalogue entries. Yvonne Szafran and Sue Anne Chui’s essay highlights Andrea’s practical methods and processes, from preparing supports for painting to the use of tools for enlarging or reducing designs. A small but important section here explores the adaptable use of cartoons, drawings made on the same scale as the intended painting for the purposes of transferring designs across multiple supports. Artists re-using previous designs is common knowledge to art historians studying the Renaissance period. However, it rarely becomes the subject of extensive scholarly discourse, especially concerning the sixteenth century; the catalogue is unique in this sense. In Andrea’s case, it is immediately obvious when one compares the Panciatichi Assumption with the Passerini Assumption (both Galleria Palatina, Florence), or between the Borgherini Holy Family (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and the similarly-dated panel of Charity (National Gallery of Art, Washington DC).

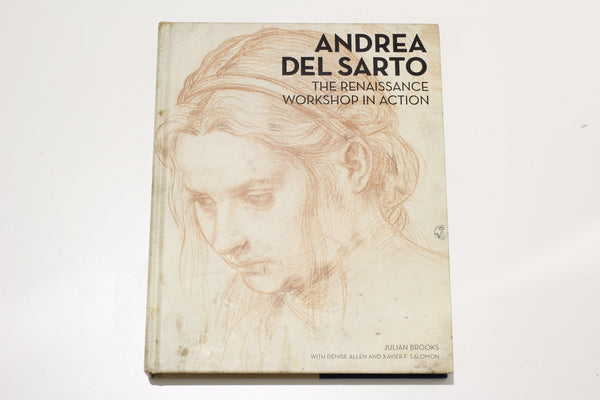

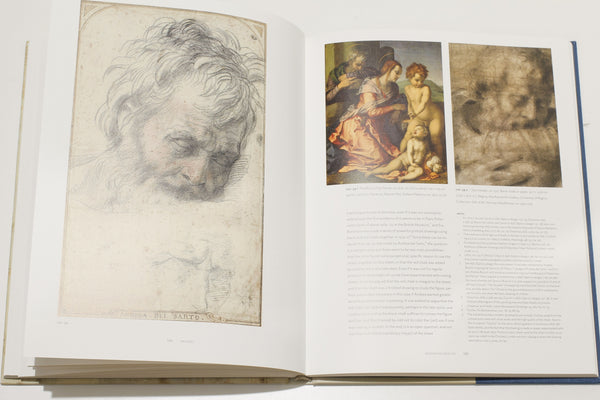

In other cases, there are multiple versions of the same composition – for example, The Sacrifice of Isaac has three versions in Cleveland, Madrid, and Dresden – raising questions about prime versions of compositions and the role of the workshop. In the case study dedicated to the Sacrifice of Isaac, Brooks notes that they were all based on the same cartoon, despite being differing sizes. Though unfinished, the Cleveland version is generally regarded as the first of the three. Readers are also treated to fascinating double-page spreads showing the Cleveland and Madrid versions next to their infrared reflectograms (IRR); this allows us to see the underdrawings and changes (pentimenti) made throughout the painting process. A brief but detailed appendix by Marcia Steele about the Cleveland picture follows, summarising technical observations between the painting and its IRR.

The Dresden Sacrifice of Isaac has also been reproduced but its IRR serves a different purpose a few pages later, when it is revealed that cartoon transfer lines matching elements of Pietro Perugino’s The Marriage of the Virgin (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Caen) have been identified beneath the painted surface. This discovery suggests that Perugino or his workshop may have begun working on a replica of the Caen painting, abandoned it, and the panel eventually made its way into Andrea’s hands who turned it upside down and re-used it.

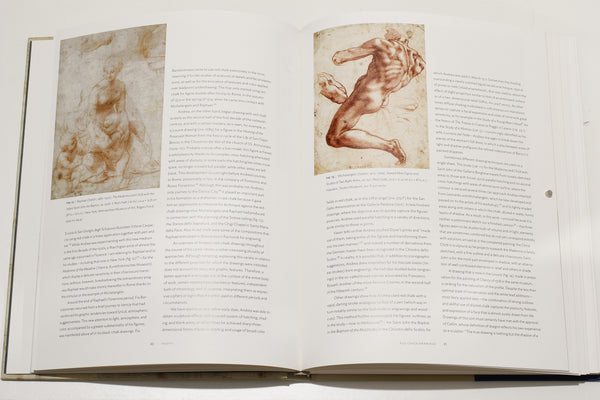

In the essay by Marzia Faietti, Andrea’s red-chalk drawings are held as examples of a synthesis between two opposing theoretical approaches to art-making: Florentine disegno (meaning both design and drawing) and Venetian colore (colour). This was a common debate in the sixteenth century among intellectuals. Many believed the linear precision of disegno was more important than the rendering of insubstantial planes of colore. Disegno would go on to have a deeper association with divine creation, expounded by Vasari in his Lives of the Artists in connection with Michelangelo.

Faietti swiftly introduces the reader to the medium of red chalk and how artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael have used it. More importantly, however, are the unique properties that the medium possesses and how Andrea exploited them; it is hard enough to be sharpened for rendering minute details, yet also has a shallow depth of tone that allows for soft rendering of tones, perfect for life studies and explorations of light and dark. She goes on to highlight recurring graphic features in Andrea’s drawings – hatching systems, shaded areas, combinations with other media – and lands on a perfectly accurate observation: ‘Andrea’s drawing strokes are never decorative; they are always aimed at rendering the effects of light and three-dimensionality in order to imitate nature.’ Although this may be said of other artists, Andrea’s extant drawings expose his assimilation (and invention) of a complex repertoire of graphic codes to record his surroundings.

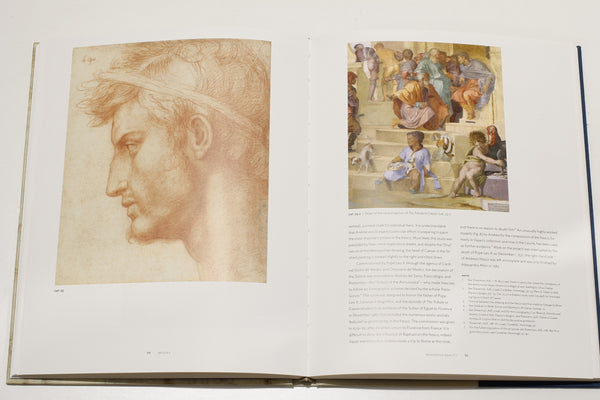

Two of the essays in the catalogue tackle comments made by Vasari in his biography of Andrea, one of the longest in The Lives of the Artists, covering 40 pages in the 1550 edition and 55 pages in the 1568 edition. The biographer mentions Andrea’s apparent unwillingness to undertake the challenge of assimilating the antique and contemporary works in Rome during his brief stay, but Dominique Cordellier’s analysis tells a rather different story. Various sheets of drawings show that the artist copied details from contemporaries like Michelangelo and Baccio Bandinelli; his interest in the latter’s design for The Massacre of the Innocents engraving by Marco Dente da Ravenna says much about his curiosity towards architectural compositions and spatial constructions. His Madonna paintings reveal his debt to Raphael, and studies for The Tribute of Caesar (Villa Medicea, Poggio a Caiano) demonstrate knowledge of antique portrait busts. Some of these drawings also provide circumstantial evidence, such as possible first-hand knowledge of Michelangelo’s now-lost bronze David, commissioned in August 1502 for the French Pierre de Rohan but, due to delays, entered the collection of Florimond Robertet.

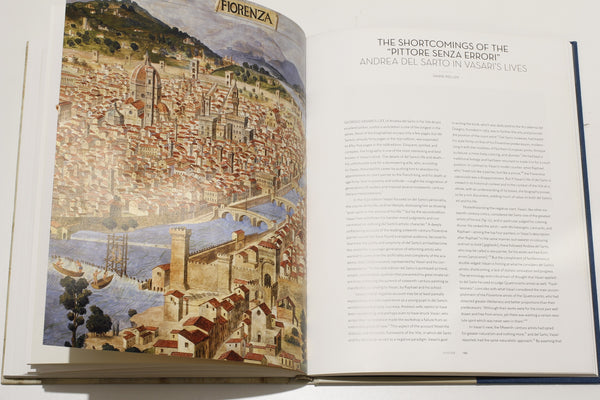

As for Sanne Wellen, she considers Vasari’s double-edged claim that Andrea was a painter ‘free of errors’ (senza errori). Although he considers Andrea one of the greatest artists of his era, he is also harking to the artist’s lack of stylistic innovation and progress. For Vasari, sixteenth-century artists needed to surpass nature and embellish it in their art. However, as Wellen astutely observes, Vasari’s use of terminology and language in his judgement of Andrea parallels the main accomplishments of fifteenth-century artists: their works aimed towards greater naturalism and nothing more. As a result, Andrea’s works possess the same naturalistic approach and sense of calm witnessed in the works of previous Florentine artists like Giotto, Masaccio, and Domenico Ghirlandaio. Vasari attributes this to Andrea’s lack of Roman experience and study of recently-excavated Antique sculptures, both untrue. Such experiences, combined with ‘resolute boldness’ and abundant invention, helped to characterise the bella maniera (beautiful style) of sixteenth-century artists, a style which Vasari felt Andrea’s art did not belong.

The Lives does more than just comment on the art of a long list of individuals; it also offers glimpses into their personalities, something which must always be taken with a grain of salt. This is used countlessly to support Vasari’s personal agendas in the Lives. For example, Wellen speculates the possible implications of mentioning a Florentine artist by name when recounting an artistic challenge presented to Perino del Vaga in the Brancacci Chapel of Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence, painted by Masaccio and Masolino in the early fifteenth century. Andrea del Sarto is rumoured to have been the master who challenged Perino but mentioning him by name would have contradicted Vasari’s idea of Andrea as having a ‘timidity of spirit and a sort of humility and simplicity in his nature’, something which the biographer attributes to Andrea’s reluctance towards artistic challenges. Mention has also been made of how Vasari’s biography of Andrea changes between the 1550 and 1568 editions, reflecting the intellectual climate.

The last section of Wellen’s essay relates the notion of fiorentinità in Andrea’s character and lifestyle with certain characteristics associated with Florentine communal life in Vasari’s view. These include a lack of courtly ambitions, ‘uncourtly’ manners, and a tendency towards conviviality and pleasure. This is extended towards a discussion of Vasari’s negative perceptions of members of the compagnie di piacere, which included Andrea del Sarto and his circle of artist friends. Members of such clubs put on spectacles and lavish dinners, time-wasting activities which Vasari saw as impeding the progression of the arts and the advancement of the artist’s social status.

More importantly, Vasari’s harsh criticism of Andrea’s character is made clearer by understanding the social behaviour of Andrea’s pupil Jacone. He spoke in slang, visited artists’ workshops to criticise their work, and ‘always had his mind set more on giving himself a good time and every possible amusement, living in a round of suppers and feasting with his friends’. In Vasari’s view, Jacone was an artist who had become so lazy and terribly-mannered that his abilities had dropped; such a person would have negatively impacted Andrea’s lifestyle and development as an artist. Vasari’s description of Jacone echoes qualities associated with Andrea, and such a tale comes with a moral to lead a more honourable life in order to gain wealth and fame.

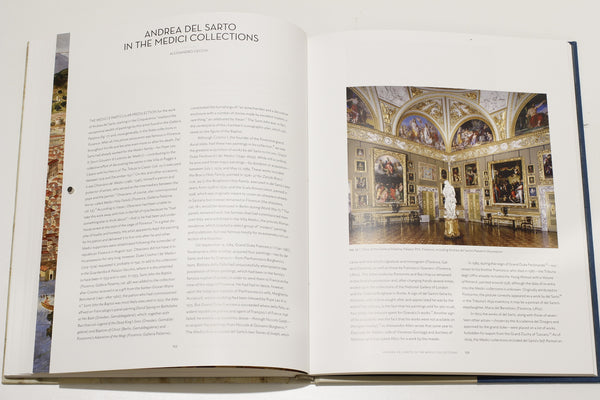

Finally, the extent of Andrea del Sarto’s popularity is made clear in Alessandro Cecchi’s examination of his works in Medici collections. It follows a straightforward, chronological format, beginning with Pope Leo X’s invitation to contribute to the decorations of the salone in the Villa di Poggio a Caiano. There are anecdotal observations suggesting Andrea’s level of fame and appreciation: by the end of the sixteenth century, his paintings were being sold for 360 scudi (four times the amount for works by the much-respected Francesco Granacci), and his works were not available on the open market.

The essay is full of circumstantial evidence which makes for fascinating insights into the dramatic stories behind paintings like the damaged Annunciation altarpiece (Galleria Palatina); it was originally from the destroyed Augustinian church of San Gallo, before being removed in 1627 from its second home in the church of San Jacopo tra’ Fossi at the request of Archduchess Maria Maddalena of Austria, widow of Cosimo II de’ Medici. It has also been observed that the Medici collections of Andrea’s drawings seem almost entirely to have been part of Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici’s holdings, with a further six added by Grand Duke Cosimo III.

The catalogue is richly illustrated with great attention paid to comparative works, allowing the reader to seriously contemplate the technical skill of Andrea del Sarto’s draughtsmanship and the role they played in the planning process. At the front, there is a brief timeline of key historical events and moments in Andrea’s life, compiled by Laurel Garber, and the back has a full record of the works exhibited at both venues. The first 40 catalogue entries are engaging with their vivid descriptions of Andrea’s technique and influences, but it is the last 15 entries which really offer a more complete view of the workshop in action. Naturally, this is due to the exhibition’s opportunity to exhibit four paintings alongside their preparatory drawings. Where technical studies have been conducted on The Madonna of the Steps (Museo del Prado, Madrid), The Sacrifice of Isaac, and the Medici Holy Family (Galleria Palatina), the chance to view their IRRs and related drawings offers a significant understanding into Andrea’s revisionist tendencies after the cartoon stage, as well as their later variants. The catalogue is, therefore, an indispensable resource for the study of Renaissance workshop practices, offering ground-breaking technical and documentary research on the artist, as well as precise details into Andrea’s way of thinking and producing works of art.

Our thanks to the Getty publishing team for a review copy of this book.